A recent poll of U.S. Catholics reveals that they are more concerned about climate change and the global refugee crisis than about the global persecution of Christians.

According to Aid to the Church in Need, “Christians are the victims of at least 75 percent of all religiously motivated violence and oppression.” The report adds that some 215 million Christians face severe persecution, mostly at the hands of Muslims.

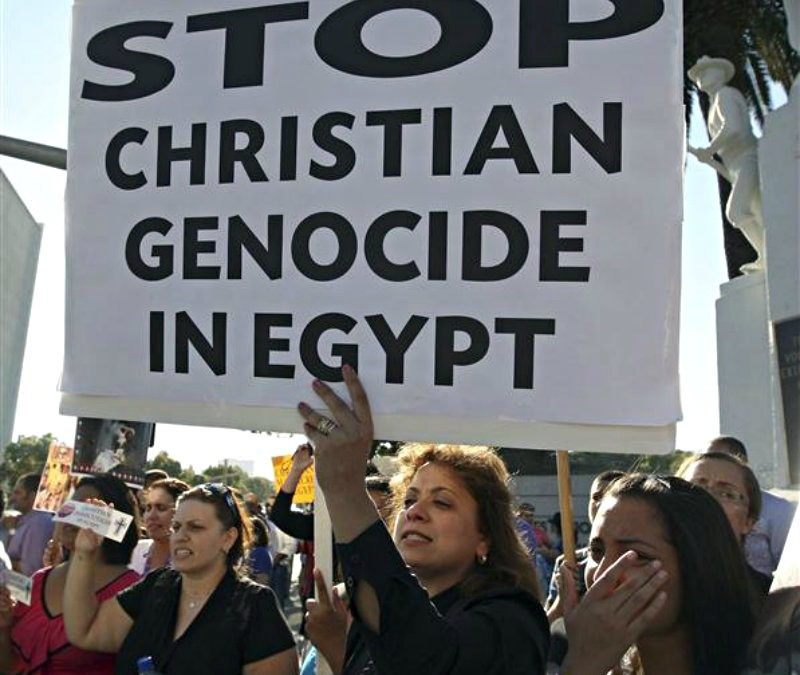

Why do Catholics rank the persecution of Christians as a lesser concern than climate change, poverty, human trafficking, and the refugee crisis? One reason might be that we live in an image-oriented society, and images of people in trouble personalize the crisis in a way that text alone does not. Pictures of people in danger from hurricanes, floods, and forest fires are omnipresent—a constant reminder of the dangers supposedly caused by climate change. By contrast, images of persecuted Christians are in short supply. Hence, their crisis seems less immediate.

According to the ACN figures, there are many more Christians in danger of persecution than there are refugees endangered by the hazards of migration. Yet the plight of the refugee remains a higher priority for Catholics. That’s because pictures of refugees abound, and pictures of persecuted Christians do not. Moreover, if you can believe the pictures, the great majority of these refugees are women and children. In addition, Catholics are given the impression by their bishops that the plight of the refugees is somehow the fault of hard hearted Westerners who fail to follow Christian injunctions. That, of course, makes the crisis all the more personal and immediate.

There are several reasons why photos of persecuted Christians are less readily available. One reason is that there may be danger involved in taking them or acquiring them. Another possibility is that there is less demand for them. Pictures generally accompany stories in newspapers or on television news. But stories about Christian victims seems to be a low priority for the media. And because there are fewer stories on the subject, there is less demand for images to accompany them.

On the other hand, stories (and, hence, pictures) about immigrants and refugees are a more lucrative business. There is actually a market for them. For example, it was recently revealed that the Irish government has been paying journalist to write positive stories about Project Ireland 2040, a 116 billion Euro plan to bring in a million migrants to Ireland. Since the population of Ireland is only 4.7 million, that’s a hard sell. But with the help of the media, the government hopes to sell it.

Likewise, America’s Catholic bishops have been paid as much as 90 million per year to resettle refugees. That may be a part of the reason that the bishops are currently involved in a massive campaign to highlight the plight of migrants and refugees. It may also explain why the foyers of Catholic churches are filled with pictures of migrants rather than pictures of persecuted Christians.

There’s another reason we don’t often see pictures of Christian persecution, and it’s a bit more sinister. There appears to be a deliberate attempt on the part of government and media to suppress news of Christian persecution. That’s because in order to tell the full story you would have to get into the bothersome detail of identifying the persecutors. That, in turn, would put Islam in a bad light, and that is something that media, government, and Church elites would prefer not to do.

Take the case of Marine Le Pen. She ran for French President in the last election, but she’s also run afoul of the French courts for tweeting violent images. The photos she posted were of Islamic State executions. As a result, she now faces a heavy fine and a possible three year prison sentence—which may require a reworking of the old maxim into something like “a picture is worth a thousand days (in jail.)”

Last year it was revealed that the French government had also suppressed pictures of the brutalized victims of the jihad attack on the Bataclan Theatre. In addition, it was reported that a French priest, Fr. Guy Pages, had been arrested for embedding photos on his website of the carnage at the Bataclan. In short, the authorities don’t seem to make any distinction between the perpetrators of the evil deed and the ones who expose it.

But let’s get back to Le Pen. She had posted the execution pictures in the first place to counter charges that her political party was just like ISIS. The three photos did not involve the execution of Christians per se, but such photos (and videos) exist, and one supposes that if she had posted them the result for her would have been the same.

Although she was charged with “distribution of violent images,” it’s likely that the chief problem was not the violence itself, but the fact that the violence was being committed in the name of Islam. Thus, the posting of the pictures could be taken as a criticism of Islam—something that is beyond the pale in polite French society. The images might also remind the French public that the government’s policy of facilitating mass Muslim migration is not such a good idea.

From the way the French press described Le Pen’s actions, one would think she was the one responsible for the gruesome murders. Her actions were branded as “insensitive” and “shameful.” Yet it’s doubtful that the authorities were really worried about insensitivity. Her real crime in their eyes is that she had exposed an ugly aspect of the ideology that the authorities themselves were importing into French society.

In a way, it’s reminiscent of the protests against the “insensitive” images of aborted babies that pro-lifers carried in demonstrations. Of course, the real problem with the pictures was not that they were insensitive, but that they exposed the reality of the procedures that the pro-choice organizations were endorsing. In this regard, it’s important to note that it was not until ultrasound pictures of babies in the womb became widely available that the tide began to turn against abortion.

It’s no wonder that the Catholics who were polled about the five global concerns put persecution of Christians at the bottom of the list. Most Catholics don’t realize how brutal, oppressive, and widespread this persecution is. Nor do they realize how deeply involved Muslims are in the oppression.

They don’t realize because the full picture had been withheld from them. Moreover, it’s not just governments that suppress negative news about Islam. Big businesses—particularly social media giants—do the same. Google makes it difficult to find Islam-critical sites, Facebook shuts them down, and YouTube censors them.

One example comes from Raymond Ibrahim who, because of his extensive knowledge of Islamic history and his fluency in Arabic, is a particularly effective critic of Islam and Islamists. In a recent article, Ibrahim discusses YouTube’s practice of putting restrictions on Prager University for producing videos that violate their “community Guidelines,” and are thus “not appropriate for a younger audience.”

One 5 minute video that Ibrahim made for Prager University is entitled, “The World’s Most Persecuted Minority: Christians.” Most of the video consists of Ibrahim talking to the camera in a calm and measured manner. The rest is maps, pie charts, graphs, and occasional stick figures who are no more threatening than a 5 year old in a Halloween costume. Yet Ibrahim’s video is identified by the “YouTube community” as “inappropriate or offensive to some audiences.”

One suspects that the really offensive thing about Ibrahim’s fact-filled presentation is that it throws a wrench in the media’s positive narrative about Islam. In his video, Ibrahim notes:

If this were happening to any other group besides Christians, it would be the human rights tragedy of our time. There would be loud worldwide calls for action.

But there isn’t. Instead there is silence: a deliberate attempt by government, media, and Internet giants to suppress the story and the pictures of persecuted Christians. In the future, we can expect more and more attempts to withhold videographic information about the Islamic persecution of Christians on the grounds that it’s not appropriate for us to know. It may be true that one picture is worth a thousand words—but that’s only if you get to see the picture.

This article originally appeared in the March 13, 2018 edition of Crisis.

Photo credit: Christianpost.com