In my last piece for Crisis, I emphasized the importance of casting doubts on Islamic beliefs just as we cast doubts on Soviet Communist ideology during the Cold War.

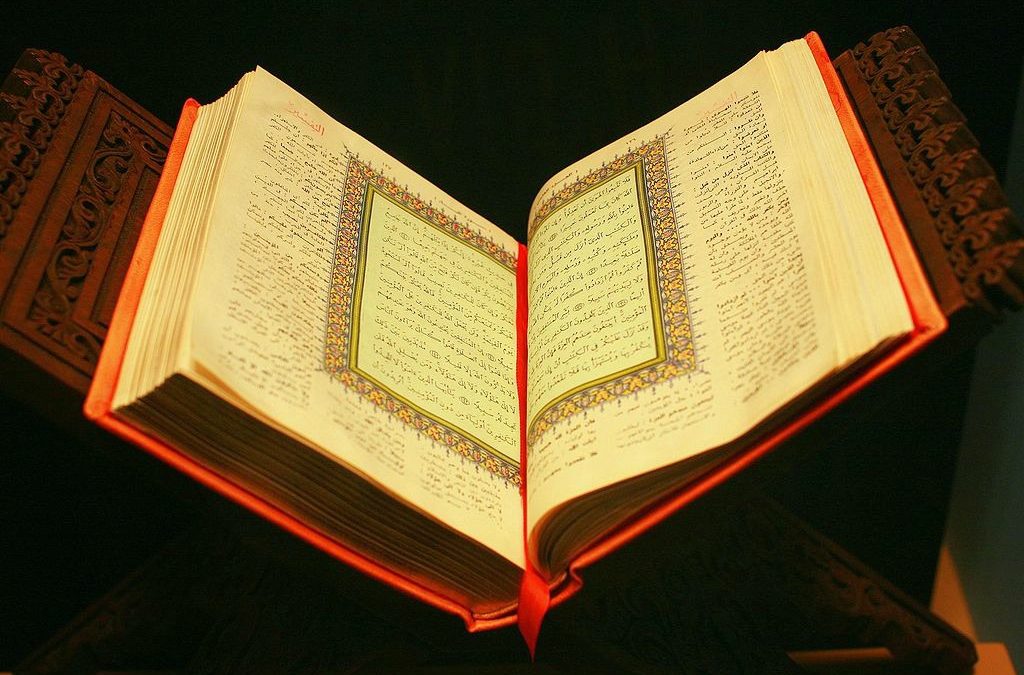

With that in mind, let’s talk about the Koran. It’s the fountain from which the ideology flows. It is quoted incessantly by terrorist leaders and imams alike, and it provides the motivation for both armed jihadists in combat fatigues, and cultural jihadists in business suits.

So it would seem logical for those threatened by Islam to cast doubts on the Koran. If the Koran came to be seen as a man-made fabrication rather than a direct revelation from God, the prime rationale for jihad would dissolve. Since the authenticity of the Koran rests on a very fragile foundation, the case is not difficult to make.

One would think, therefore, that Western governments would have teams of experts working on the matter ’round the clock. More to the point, one would think that Christian theologians and scripture scholars would be applying all their skills to a historical and textual critique of Islam’s “holy” book. For one thing, scripture is their area of expertise; for another, Christians are the most persecuted religious group in the world. And most of that persecution is at the hands of Muslims who claim that the Koran provides justification for their deeds.

Assuming that these experts are chomping at the bit, just waiting for a little direction, here is a suggestion: focus on the literary quality of the Koran. Why? Because, other than an occasional lyrical passage, the Koran doesn’t have much in the way of literary quality. Yet, its literary quality is the main argument for the authenticity of the Koran. “Who else but God,” ask Muslim scholars, “could have written such an inimitable masterpiece?”

Certainly not Muhammad. He is traditionally (and conveniently) considered to have been illiterate. Muhammad was merely the conduit through which the divine revelation was passed—or so Muslims believe. Actually, they don’t have much choice in the matter, since the Koran has already issued an “I-can-beat-any-book-at-the-bar” challenge. Sura 2:23 says, “If you doubt what we have revealed to Our servant [Muhammad], produce one chapter comparable to it.” The challenge is repeated with slight variations in several other verses.

But to anyone who has read a literary masterpiece—say, something by Shakespeare, Tolstoy, or Dickens—it’s an astonishing claim. There are many striking passages in the Koran, but for the most part it is tedious, repetitive, and didactic. Don’t take my word for it. Here are some scholarly observations:

His characters are all alike, and they utter the same platitudes. He is fond of dramatic dialogue, but has little sense of dramatic scene or action. (C.C. Torrey, The Jewish Foundation of Islam, New York, 1933, p. 108.)

The book aesthetically considered is by no means a first-rate performance … indispensable links, both in expression and in the sequence of events, are often omitted … and even the syntax betrays great awkwardness… (Theodore Noldeke in Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th ed., Vol. 15, pp. 898-906.)

And here’s a more recent assessment by Thomas Bertonneau:

How to describe it? The prose is unadorned, utilitarian, banal, and prone to use the imperative tense until one tires of the ceaseless exhortation.

All of which is a sad commentary on God’s ability to express himself—assuming, as Muslims do, that God wrote the Koran.

But it’s not just the mind-numbing repetition and the eye-glazing prose. The deeper problem is that the Koran just doesn’t hang together. It’s almost completely lacking in chronology, continuity, and—for want of a better word—plot.

This lack of coherence may explain why the Koran is arranged arbitrarily, with the longest chapters coming first, and the shortest coming last. Apparently, the compilers of the book gave up on trying to give it any rational order. As one of its translators notes, “scholars are agreed that a strictly chronological arrangement is impossible.”

The Koran’s lack of sequence and continuity extends to the stories within it. The Koran borrows heavily from stories in the Old Testament, invariably gives them a new twist, but fails to do them justice. The narrator will often break off in the middle of a story to tell another story, or to provide a lengthy commentary that is, at best, tangentially related to the story, or he will interrupt the story with a description of the beauty of creation, or—more often—with a description of the fires of hell. Examples of masterful storytelling are not difficult to find. Try The Arabian Nights, The Brothers Grimm, or the short stories of Leo Tolstoy or Jack London. Just don’t expect to find anything remotely comparable in the Koran. As Professor Bertonneau notes, “The compiler of the Koran lacks any talent for storytelling…”

But, according to Islamic teaching, “the compiler of the Koran” is none other than God himself. Yet, hardly any of his stories are fully developed. Indeed they are more like story fragments—a series of unconnected episodes dropped at random into the text. In addition, the characters are so poorly developed that they are practically interchangeable. Unlike the characters in the Bible stories, they lack personality.

The difference in storytelling ability between the author of the Koran and the authors of the Bible is most in evidence when we compare the Koran’s story of Jesus with that found in the four Gospels. The contrast between the two Christs is startling. The story of the life of Jesus as told by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John has been justly called “the greatest story ever told.” Even those who don’t accept the divinity of Jesus recognize him as perhaps the most extraordinary man who ever lived.

And the Jesus of the Koran? Well, the most charitable thing to say is that there is simply no comparison. There is no comparison because the Gospels tell a story and the Koran doesn’t. The Koran can’t very well tell the story of Jesus because the main character is largely missing from the narrative. After some promising passages about his birth, Jesus puts in very few subsequent appearances. Moreover, when he does appear in the pages of the Koran, Jesus bears little resemblance to a real person. He is an entirely one-dimensional figure.

In his attempt to portray Christianity as a life-denying religion, the poet Algernon Swinburne described Jesus as the “pale Galilean.” But if you’re looking for a real pale Galilean, look up the Jesus of the Koran. Indeed, he’s so pale, and so lacking in substance, that he could be mistaken for a ghost. In a half dozen or so places in the Koran, he appears out of nowhere to utter some cryptic pronouncement or other, and then disappears again into the ether. The Jesus of the Koran is a pale creation indeed. You can’t even call him a “pale Galilean,” because there’s no mention of Galilee in the Koran—and no mention of Bethlehem, Nazareth, Jerusalem, or Jericho. Peter? Pilate? Herod? Judas? Mary Magdalen? They’re not there either. The wedding feast at Cana? The Sermon on the Mount? The Last Supper? Nope. The Koran’s “account” of Jesus is devoid of context. There is no setting, minimal description, and very little detail. To borrow a phrase from Gertrude Stein, “There’s no there, there.”

The Jesus of the Gospels is a recognizable human being. The Jesus of the Koran is more like a disembodied voice, somewhat reminiscent of the phantom-like Jesus who appears in the Gnostic Gospels. Why then did Muhammad include Jesus in the Koran? Most probably because he saw the New Testament account of Jesus as a threat to his own self-promotion. If what the Gospels say about Jesus is true, then there is no need for another prophet or another revelation. So whenever “Jesus” is mentioned in the Koran, it is almost always for the purpose of establishing that he was just a man (e.g., 4:171, 5:17, 5:75, 5:116-117).

The Koran is supposedly a revelation, but the only new thing it reveals is that Muhammad is the prophet of God. The Koran doesn’t add anything to our knowledge of God that is not already present in the Old Testament. It mainly serves as a vehicle for establishing Muhammad’s status as a prophet. Although Muhammad is mentioned by name only four times, he is mentioned on almost every other page as “The Apostle,” “The Messenger,” or “The Prophet.” Next to Allah, he is the main character.

All this attention to “messaging,” however, is—to return to our main theme—at the expense of the Koran’s literary quality. Once again, the Koran has precious little to say that hadn’t already been said by other prophets. But having established himself as a prophet, Muhammad had to keep the revelations coming in order to maintain his reputation as God’s final messenger. This helps to explain the constant recourse to repetition: repeated admonitions to “obey God and His Apostle,” repeated curses at those “who doubt Our revelations,” and repeated threats of hellfire for unbelievers—and all expressed in more or less the same boilerplate phraseology. It’s as though Shakespeare had been so taken with the phrase “to be or not to be” that he repeated it on every other page of Hamlet.

The Koran a literary masterpiece? Here’s what historian and essayist Thomas Carlyle had to say about the book:

I must say, it is as toilsome reading as I ever undertook. A wearisome confused jumble, crude, incondite; endless iterations, long-windedness, entanglement; most crude, incondite—insupportable stupidity in short!

Contrary to what one might assume, Carlyle had no animus toward Muhammad. Indeed, he considered Muhammad to be one of the great men of history, and included him in one of his most notable books, On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and The Heroic in History. On the other hand, Carlyle was also an astute literary critic who had a preference for the natural over the artificial. He could not very well ignore the patchwork nature of the Koran.

“This Koran could not have been devised by any but God… If they say: ‘He invented it himself,’ say: ‘Bring me one chapter like it.’” Thus says sura 10:37-38 of the Koran. The first thing you notice is the defensiveness. It’s exactly the type of thing that one who had invented it himself would feel compelled to say. And this is only one example. The author of the Koran never tires of reminding his audience that the Koran is a genuine revelation, not a fake one. But would the Author of Creation need to interrupt his narrative every 15 pages in order to assure his audience that it is not an invention? To paraphrase Shakespeare, “Methinks the prophet doth protest too much.”

The next thing you realize is that it’s not true. Any fairly literate person could produce dozens, if not hundreds, of chapters from existing fiction and non-fiction that surpass any chapter in the Koran. You don’t need to be a literary critic to notice the many problems with the claim that God wrote the Koran. Almost any book you pull from your shelf is—from the standpoint of composition and coherence—better written than the Koran. If God wrote the Koran, why does he display so much defensiveness? Why does he endlessly repeat himself? Why can’t he get his chronology straight? Why does he lack the literary touch—the knack for storytelling, continuity, composition, and drama that we expect to find in accomplished human writers?

Did God write the Koran? The question is bound to raise anxiety levels all around. Would it make Muslims feel uncomfortable? Hopefully, yes. We should want them to feel uncomfortable—uncomfortable to the point that they are forced to entertain doubts that God had anything to do with the composition of the Koran.

Considering what’s at stake, this is not a time to shy away from the question. If the Koran is the chief motivating force behind Islamic aggression, then the Koran should not be above discussion. Rather, Muslims should be encouraged to reflect critically upon the facts of their faith.

The doctrine that God wrote the Koran is untenable on many counts. Muslim scholars have painted themselves into a corner with the argument that the Koran is a literary masterpiece of unmatched perfection. Non-Muslims, if they value their own survival, ought to take advantage of the weakness of this indefensible position. The fact that in recent years the Koran has been largely shielded from such an inquiry is an indication of how much cultural ground has been ceded to Islamic beliefs. Christian scholars, theologians, and apologists have much lost ground to recover. They should not let the claim of the Koran’s divine authorship go unchallenged.

This article originally appeared in the August 10, 2018 edition of Crisis.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons